THE BELL

& HOWELL 2709

Bell &

Howell Company, Chicago, Illinois 1912 - 1958

The

Bell & Howell Company was formed in Wheeling, Illinois in

1907, by Donald Joseph Bell, a motion

picture promoter and projectionist and Albert

Summers Howell, an engineer and machinist. Both had previously worked

together, repairing motion picture machines and this would continue under the

new company. During this period,

Chicago, New Jersey, New York and to some degree Jacksonville, Florida, became

the earliest areas of motion picture production before the migration of

filmmakers to Hollywood.

Albert Howell made patented improvements to the frame

registration mechanism on George K. Spoor's Kinodrome projector (Patent No.

862,559 dated August 6, 1907), which had originally been built by Donald Bell

for Spoor about 1897/1898:

Source:

U.S. Patent and Trademark Office

Source:

U.S. Patent and Trademark Office

Per an article in The

International Photographer, April,1929, the company's first

hand-cranked 35mm motion picture camera was referred to as their "Box

Model Camera". Equipped with 200-foot internal magazines, it was built in

late 1907 and sent to Essanay Studios.

Essanay, founded that same

year in Chicago by George K. Spoor and Gilbert M. Anderson, was originally

known as the Peerless Film Manufacturing Company. On August 10, 1907, the name

was changed to Essanay, the name derived from Spoor's and Anderson's first

initials "S" and "A".

Constructed with a wooden body typical of professional cameras of

the day, only eight were reportedly built:

Bell & Howell's first 35mm motion

picture camera, the Model A from 1907

As to why the camera's construction changed, Jack Fay

Robinson's book, Bell & Howell

Company, A 75 Year History states that "The first Bell &

Howell cinematograph camera was produced in 1910. It was made entirely of wood and covered with

black leather. The following year, moving picture explorers, Martin and Osa

Johnson, wrote that their camera had been destroyed by termites and mildew in

Africa." This version of the story has been challenged, by the suggestion

that the Johnsons hadn't traveled to Africa before 1920. Whatever the real truth, this first model was

short-lived and Bell & Howell was determined to build a more indestructible

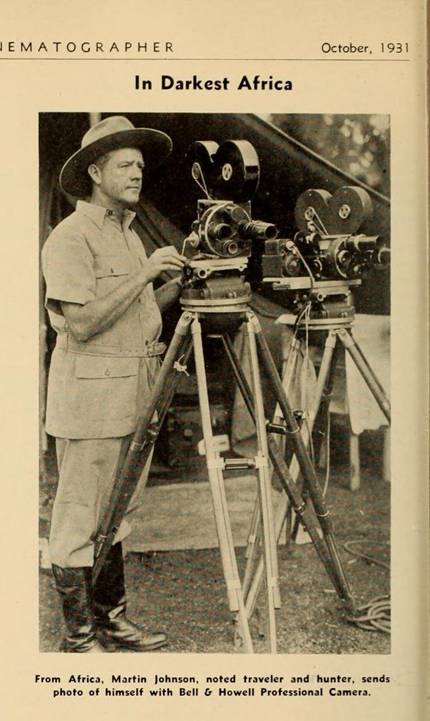

camera. As seen below, Martin Johnson

would go on to use the new 2709:

From The American Cinematographer,

October, 1931

The

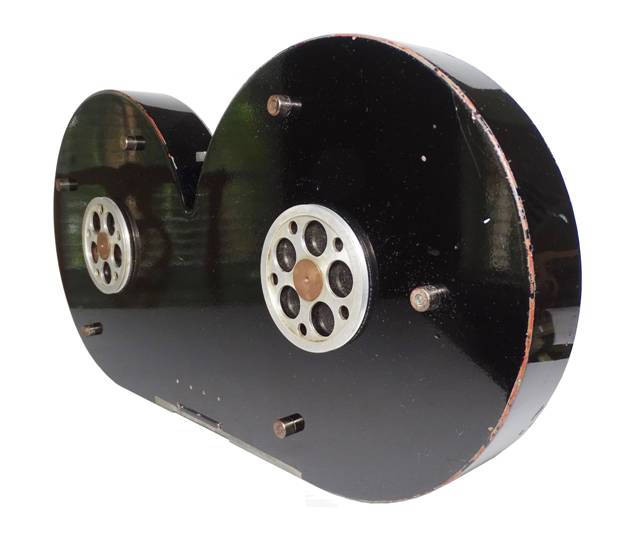

new 2709 B was made of cast aluminum weighing about 27 pounds, with the now

familiar "Mickey Mouse ears" shaped film magazines. The silhouette of

these style magazines, whether mounted on a Bell & Howell or a Mitchell, is

and forever will be Hollywood's most iconic symbol.

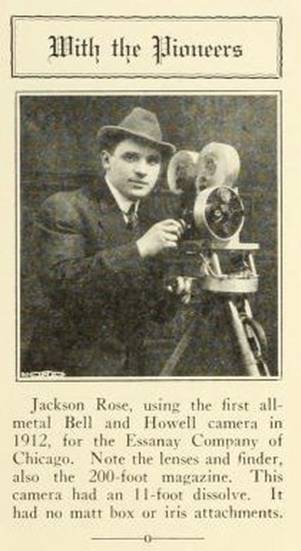

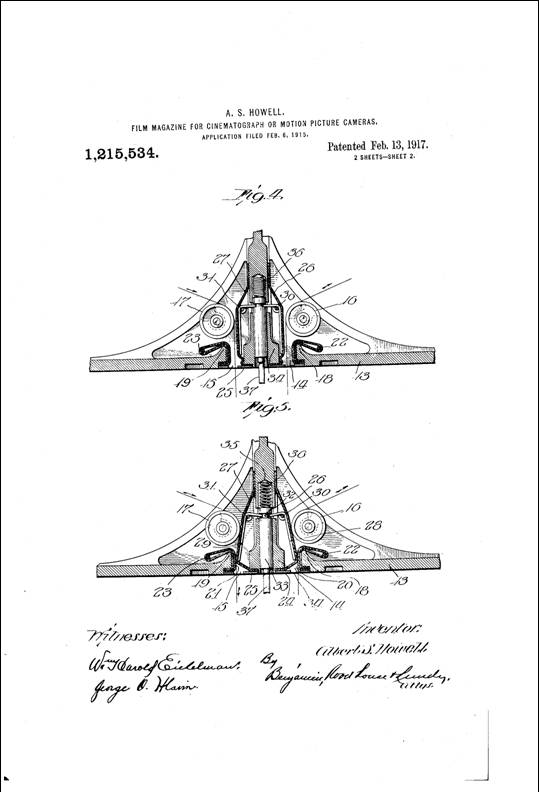

Below,

Jackson Rose, ASC, is shown with one of the very first 2709's. The first 2709's (reportedly twelve) were produced

with heavier turrets and a number of other design differences that would change

on subsequent cameras. This heavier

turret is evident in the clipping below:

From The International Photographer, April, 1929

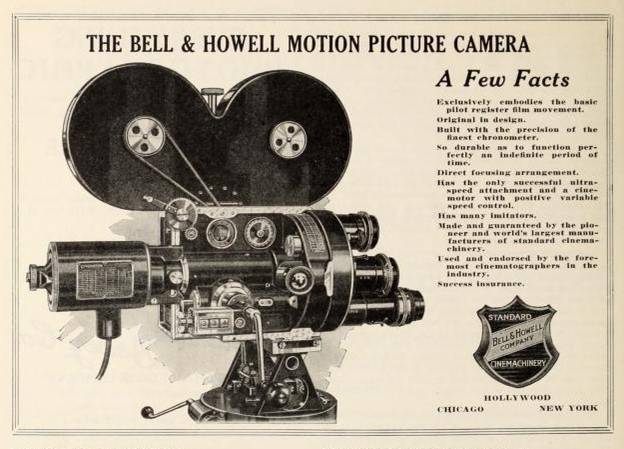

Introduced

by 1912, the 2709 incorporated such state of the art features as a 4-lens

turret, permitting the quick change of lenses simply by rotating the desired

one into position. It also featured a film registration system whereby each

frame was drawn in by a claw mechanism and held steady by the gate during

exposure. Equipped with its standard Unit-I shuttle movement, it was also

offered with an Ultra-Speed

Attachment (high-speed movement). Later on, the 2709 DD model made specifically

for high-speed work, came standard with this movement which was capable of 200

frames per second. Reportedly, only

twelve of these Model DD's were built.

The

2709 was also equipped with a unique sliding-rack tripod mount. This feature permitted the camera to be slid

over, so that critical focusing could take place through the selected taking

lens in its filming position. The selected lens was then rotated 180 degrees,

now being set in the taking position when the camera was slid back.

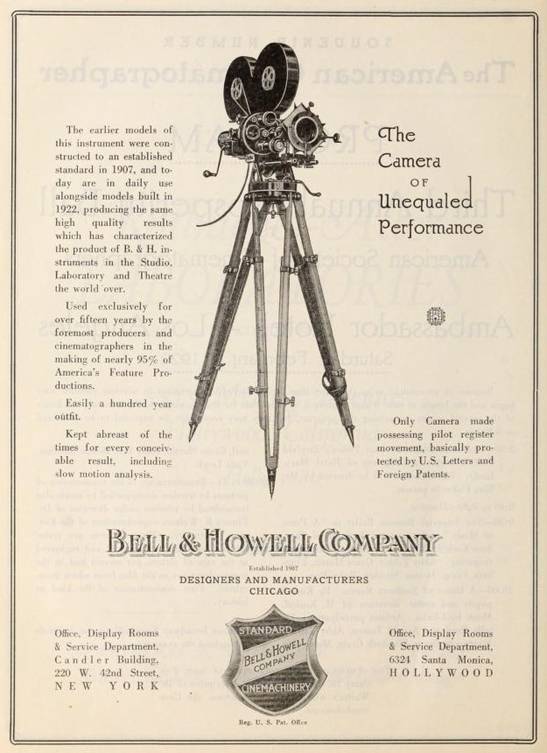

From The American Cinematographer,

February 1, 1922

Through the years, many changes were made to

the 2709 by Bell & Howell and by others, all aimed at improving the camera

in a variety of applications. With the

advent of the Mitchell Camera and the Mitchell Standard 35mm's, many of

Mitchell's components such as viewfinders and matte boxes were found to be

easier to use and many were adapted to fit the 2709 over time. One example was Bell & Howell's original

viewfinder for the 2709. When viewing through it, the image was inverted as one

would experience when using a still view camera. Introduced later on,

Mitchell's Erect Image Viewfinder reversed the image to correct this problem

and it became very popular with 2709 cameramen.

Charlie Chaplin used the Bell & Howell extensively, eventually

equipping his 2709's with Mitchell viewfinders and other components.

The 2709 was hand-cranked at 16 frames per second, which

was the industry standard at that time. In 1920, Bell & Howell introduced

their Cinemotor as an option to

hand-cranking. The Cinemotor attached at

the camera's rear, as seen below in a 1923 advertisement:

From the American

Cinematographer August, 1923

With the Cinemotor and the Ultra Speed Attachment, higher

frame speeds could be realized. Later

on, improvements were also made to the lens angle indicator. Bell & Howell's original footage counter

with tiny graduations, was difficult to read and of limited use. With the advent of Veeder counters that could

be mounted in conjunction with the crank handle or to the motor port at rear,

film production and documentation was greatly enhanced. Special effects, such as a double exposures

in transitioning from one scene to another, could now be achieved with a higher

degree of accuracy. This saved time, reduced costs and resulted in less wasted

film. Larger capacity 1,000-foot

magazines would also become available.

Most 2709's contain Bell & Howell's trademark badge

with the company's name, serial number and model number, sometimes accompanied

by another plate noting additional patents.

Today, these two plates help in establishing the date of manufacture,

and to whom the camera was originally sold.

The camera's serial number can also be found stamped on

the camera's top, beneath where the film magazine mates to the body. Having the serial number in several areas

helps to reaffirm a camera's identity and provides at least one number should

the factory badge be missing.

Reproduction badges for Bell & Howell equipment are available,

although some lack the refinement of a factory original:

Reproduction Bell & Howell

manufacturer's tag

Original

Bell & Howell manufacturer's tag

(note the more refined lettering)

The 2709 quickly became the new Hollywood standard around

1916, having eclipsed the equally famous Pathe Professional 35mm then in

widespread use since about 1908. By

1919, almost all Hollywood production was being undertaken with the 2709. It was said to have cost about as much as an

average home in 1918, making it available to the select few wealthy enough to

afford one. Charlie Chaplin was among

those that purchased the 2709 (No.

227) and his Charlie Chaplin Studios (1919-1953) would go on to own at least

four of them. Famous actress, producer

and studio owner Mary Pickford purchased No. 230. The 2709's reputation and

reliability was second to none, but with the introduction of the Mitchell

Standard 35mm and the transition from silent movies to "talkies", the

2709's inherently noisy film gate became a problem for sound production. Efforts were made to silence the 2709, either

by encasing it within a sound-proofed booth, or by wrapping the camera in

blankets referred to as "barneys". Eventually, most studios

transitioned to the Mitchell 35mm which had a quieter movement. Later on, some Bell & Howell and Mitchell

cameras would substitute metal gears with phenolic (laminated resin composite)

gears to further reduce the sound. Many

Mitchell's were "blimped" by encasing them

within a sound retardant metal clamshell.

Even as the 2709's popularity waned in Hollywood, it still remained in

use for animation and special effects work well into the 1980's. For all its improvements and modifications,

the camera's basic design remained virtually unchanged over the course of its

approximate 46-year production run.

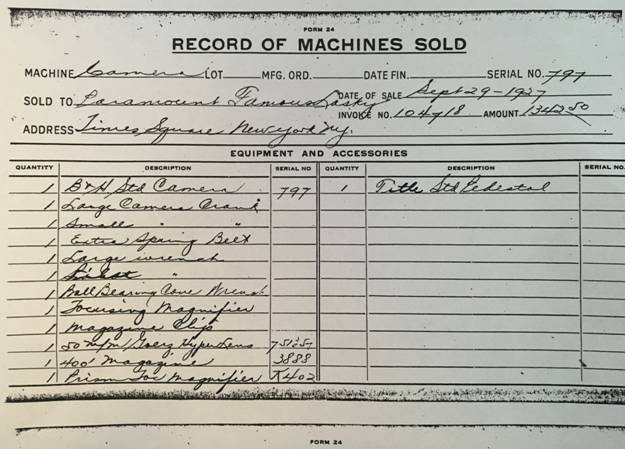

The example shown here, Bell & Howell 2709 B, Serial No.797, no longer retains its

original footage counter. It's equipped

with the Unit I shuttle movement, a 170-degree shutter, a Mitchell viewfinder

and a 2709-compatible motor that is unidentified as to maker. As shown in Bell & Howell's sales record

for Serial No. 797 shown below, this 2709 was sold to Paramount Famous Lasky, Times Square, New York, New York, on

September 29, 1927:

My Sincere Thanks to Michael Madden of handcrankcameras.com

for providing a copy of the factory record for this 2709

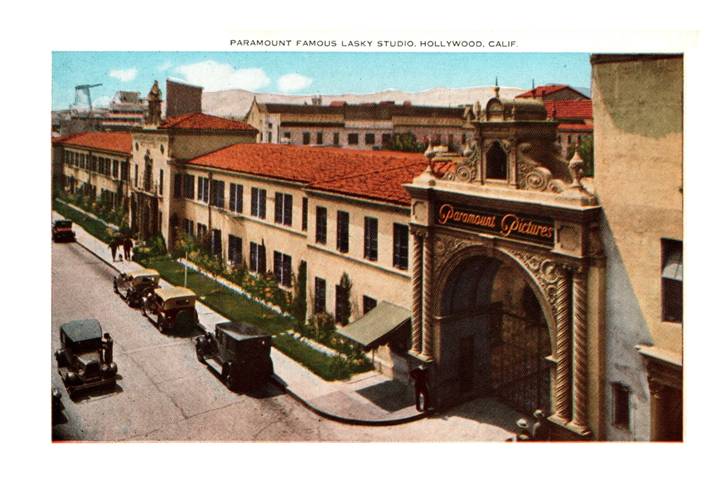

The Paramount

Famous Lasky Corporation had just been established in September, 1927, when

this camera was purchased by them. The

studio would operate under this name for three years, after which time the name

changed to Paramount Publix Corporation. By 1936, the studio would be known as Paramount Pictures, Inc., known today

as Paramount Pictures Corporation or

just Paramount.

Paramount

Famous Lasky Corporation's West Coast Studios....the

building still stands today

Paramount

Pictures Bronson Gate

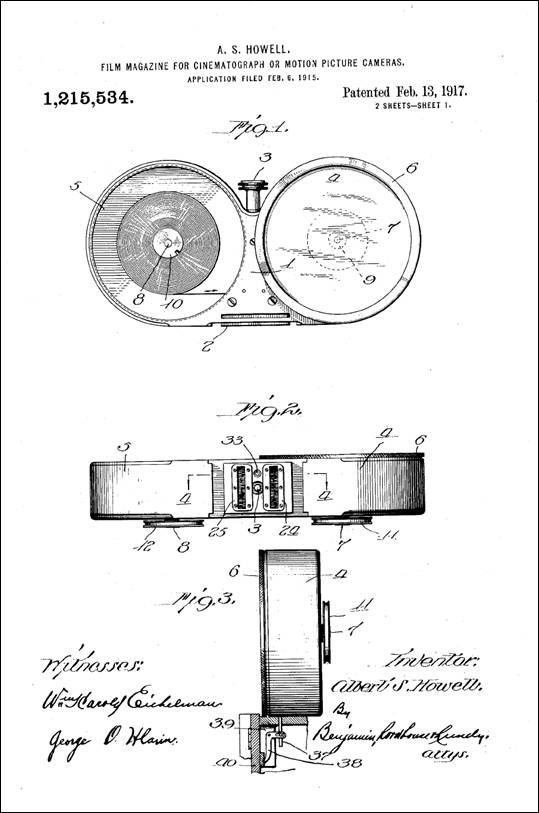

A plate affixed to the 2709 featured here, has patent

dates of September 17, 1912 ("Motion Picture Machine") and February

13, 1917 ("Film Magazine for Cinematograph or Motion Picture

Cameras"). These patents covered

the 2709's movement and a safety gate that automatically closed, when the

camera's side door was opened, preventing the exposure of film in the magazine

or the entrance of dust.

This 2709 B

seen in the opening photo with a 400-foot magazine, is mounted on a

period-correct Bell & Howell tripod from the 1920's. Shown below is the same camera mounted with

three different film magazines to illustrate their size differences:

200' Film

Magazine

400' Film

Magazine

V-Type

Bi-Pack Adaptor with two 400-foot Film Magazines

1000' Film

Magazine

Approximately 1,225 cameras of all models of the 2709

were manufactured, and very few exist as originally built. Whether original or modified, the total

number of survivors is unknown. But the

2709 in any form is very scarce, with the earliest models being extremely

rare. Prices in the 1990's remained

high, with the camera being both usable and collectible. Today, the 2709 is used more as a movie prop

or in a very limited production capacity. Some 35mm motion pictures continue to

be made, but with the film industry's transition to digital, the 2709 has

become one of the last vestiges of Hollywood's "Golden Age".

Bell & Howell letterhead 1915

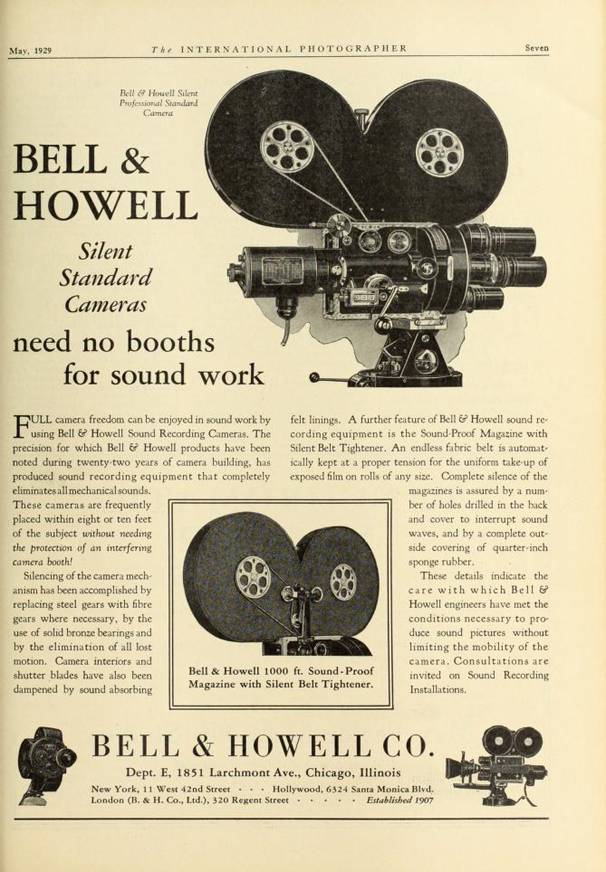

From The

International Photographer, May, 1929

1000' Film Magazine

Bell & Howell manufacturer's tag from the 1000' film magazine above

Source: U.S. Patent and Trademark

Office

Source: U.S. Patent and Trademark Office

Footage (Veeder) counter

(earlier production)

Footage (Veeder) counter

(later production)

Ultra-Speed Attachment

(high-speed movement)

Unidentified cameraman with a Bell

& Howell 2709 and what may be the earliest version of Bell & Howell's

tripod and head, probably taken in the mid-to-late teens or the early 1920's

Mack Sennett with his mother,

Catherine Foy Sinnott, June 27, 1923 standing next to

a Bell & Howell 2709

Door-mounted maker's tags are

generally seen on earlier models, versus mounted to the back of the camera's

body on later production cameras

Bell & Howell 2709 on the set of La

Boheme 1926, with left to right, Cinematographer Hendrik

Sartov, Director King Vidor, Producer Irving Thalberg

and Lillian Gish

Charlie

Chaplin filming The Gold Rush in Truckee, California, 1925 with a group

of Bell & Howell 2709's. Chaplin's

primary cameraman Roland "Rollie" Totheroh with the beard, dark sweater and knitted cap is

seen just to the left behind Chaplin

Charlie

Chaplin with a Bell & Howell 2709. The camera is equipped with a 1000-foot

magazine, a Mitchell matte box and is mounted on the first version of

Mitchell's Friction Head with a Mitchell Standard Tripod Base. Cameraman Roland Totheroh

is seen directly behind the camera to Chaplin's left.

Although

undated, the photo may possibly have been taken on April 22, 1935. It bears strong similarity to another photo

taken of Chaplin from the other side of what appears to be the same 2709, also

equipped with a 1000-foot magazine, a Mitchell Friction Head and what's

believed to be the same Art Reeves motor drive. The other referenced photo was

captioned "Actor Charlie Chaplin looks through a movie camera on April 22,

1935. He is directing, as well as acting in, a comedy tentatively titled

Production No. 5."

The

above photo is believed to have been taken on the set of Modern Times, during filming which took place between

October 11, 1934 and August 30, 1935.

Rudolph Valentino (seated at center)

on the set of The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse, 1920, surrounded by

cast, crew, a number of Bell &

Howell 2709's and one Pathe Professional at the far left

Probably mid-late 1930's panoramic photo of a cinematography

school, presumably students and instructors with what appears to be 29 Bell

& Howell 2709's. Many Mitchell Friction Heads (introduced 1928) can be

seen, along with some earlier crank heads. Most of the cameras are equipped

with only one or two lenses, which wasn't the typical 4-lens studio set-up. By

the late 1920's/early 1930's as sound pictures were now being made, the Bell

& Howell 2709 had been eclipsed by the Mitchell Standard which was quieter

and equipped with features that were either easier to use or more progressive.

As a result, the 2709 was relegated to second-unit, animation or other

specialized work. This made the 2709 much more affordable for a school teaching

the basic principles of cinematography, as by the late 1930's, a used

un-silenced 2709 could be had for about 40% of the cost of a used Mitchell

Standard.

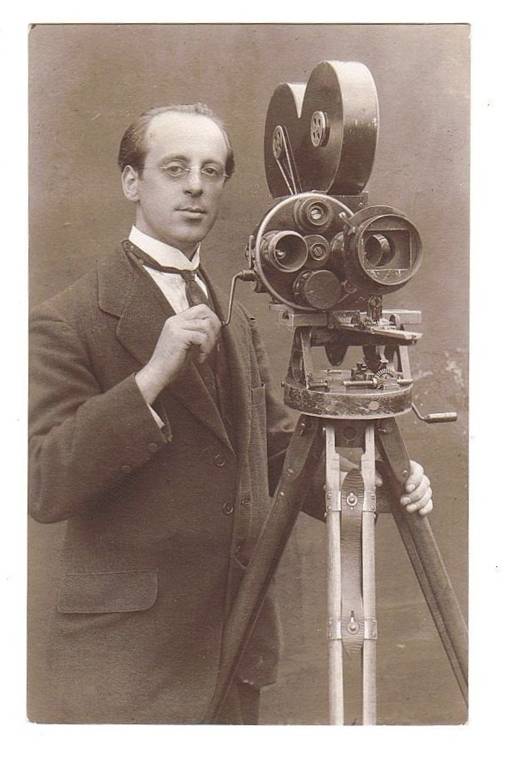

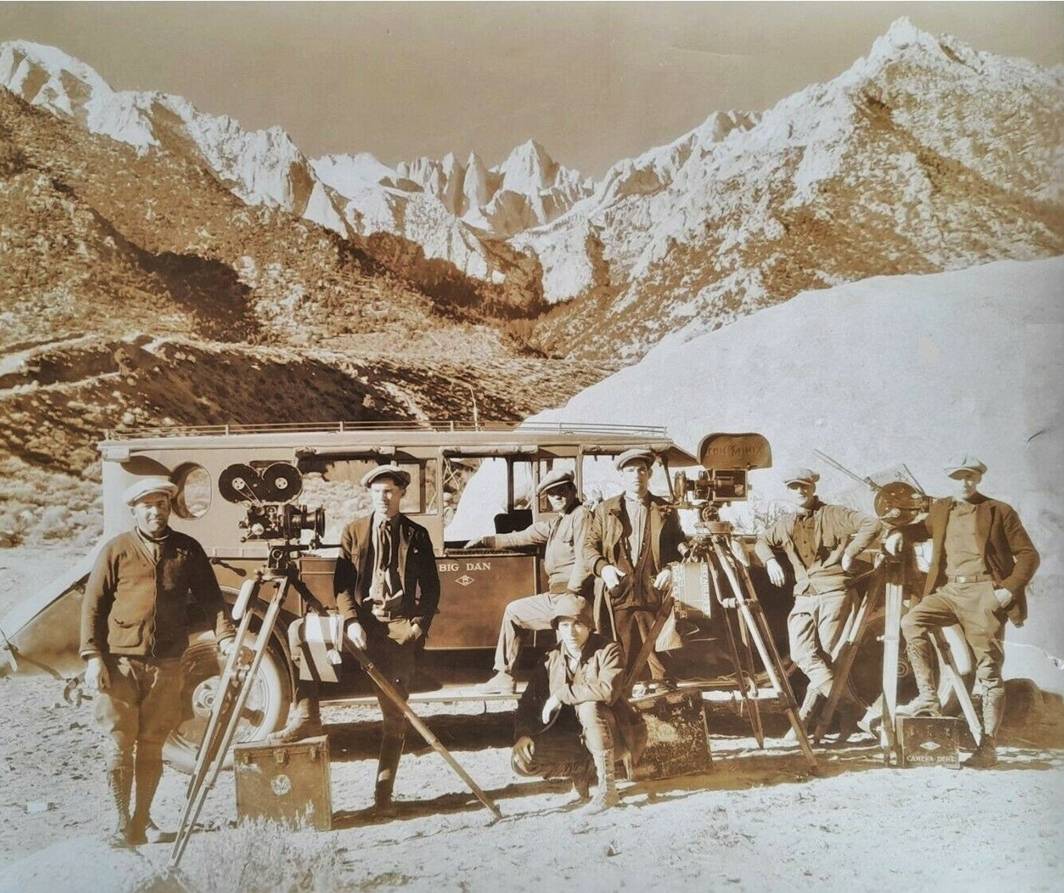

Camera

crew for the Fox Film western Riders of

the Purple Sage (1925) with two Bell & Howell 2709's and an Akeley

Camera. The photo is posed against the peaks of the Sierra Nevada mountain

range with Mount Whitney in the center background. Pictured is cameraman Daniel

B. "Big Dan" Clark (leaning on the truck) with his assistant Roland

Platt to the right of him. Clark was cameraman for most of Tom Mix's 1920's Fox

movies and would also serve as President of the American Cinematographers

Society (ASC) from 1926-1928.

The

Tom Mix name and circle "M" logo can be seen on the Bell & Howell

2709 with the leather magazine cover. Also pictured is cameraman Norman Devol, with camera second from the left. This picture has

no still code and was probably not used for publicity.

Bell & Howell

Authorized Dealer Merit Award

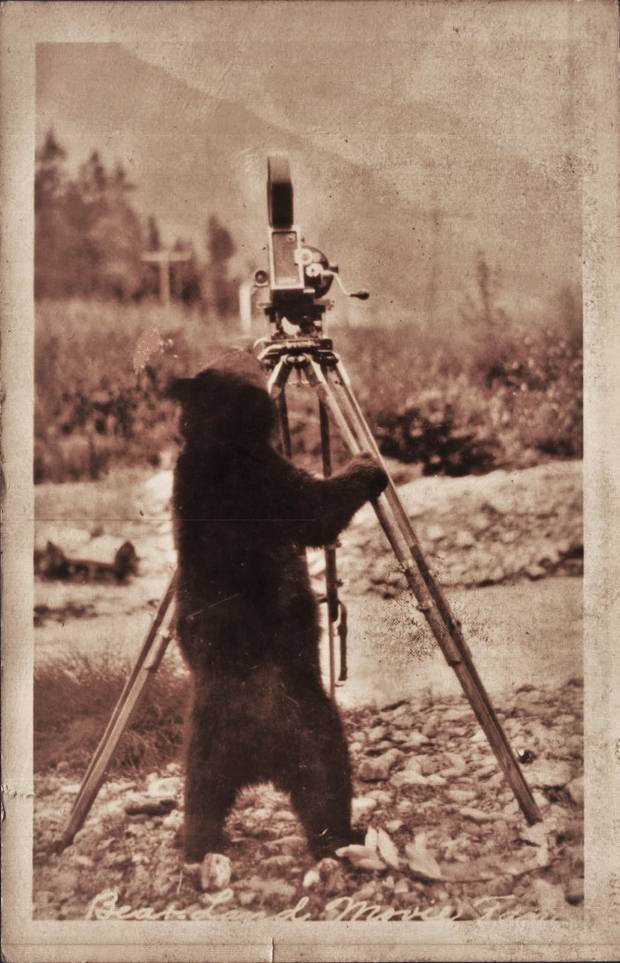

Please bear

with me while I set up the next shot!

SIDE

STORY

This

Bell & Howell 2709 was purchased on eBay, probably having been posted just

minutes before I began a search of vintage photographica.

Purchased as a "Buy-It-Now", it was essentially a hulk, having no

crank, magazine, viewfinder or lenses. I didn't even know whether the mechanism

inside was still present. But its price was a bargain and I knew it wouldn't

last long. As it turned out, the camera's mechanicals were all present and in

working condition.

And,

just when I thought this story couldn't get any better, I already had an

original 2709 hand crank and an Astro-Berlin f2.3 75mm lens for a 2709

mount. Both these items had been sitting

on a shelf, having been acquired with some 16mm movie cameras and other

miscellaneous items from an estate sale some five years earlier. I had no idea at the time, that the crank or

the lens fit the 2709. In the years

since, I've been able to acquire a Veeder (film)

counter, high-speed movement, various magazines, several lenses, a viewfinder,

a compatible motor and a Bell & Howell tripod. Acquiring this camera was

just an unbelievable find, and the beginning of what has become a great

learning experience.

Interestingly,

this 2709 was offered by a recycling firm located less than 50 miles from

Hollywood. They picked up this 2709, along with a Mitchell camera and numerous

other items, from a major motion picture studio. Likely misplaced over the

years and relegated to junk, this camera narrowly escaped being processed for

its scrap value.

Sadly,

most of Hollywood's early motion picture equipment has ended up this way. Hopefully, with a greater appreciation for

preserving our cinematic past, less history will be lost going forward. Sometimes, timing is everything, and finds

like this are still out there waiting to be discovered.

For more information on other professional motion picture

cameras, projectors and accessories, click on the "Professional Cinematography" link below: